Metal Gear Solid as Millennial Metaphor

“You’ve served your purpose. You may die now.”

It’s 2020, and no game is more relevant than Metal Gear Solid, because no game is more interested in futility. Beating most games means facing an obstacle and surmounting it after a great struggle. Beating Metal Gear Solid means being fooled into carrying out an elaborate plan on behalf of the villains before narrowly escaping with your life… Only to learn that the PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES has been in on “the plan” the whole time. You “win” Metal Gear only after a series of humiliating defeats, and your final victory is spoiled by one of the most terrifying “gotcha” lines in gaming history.

But what exactly is “the plan,” in Metal Gear Solid? The game’s plot is legendarily murky (and it’s like clear, cool water compared to its immediate successor), but it mostly involves (I think) the creation and destruction of genetic “super-soldiers.” You play as Solid Snake, a legendary mercenary and the genetically-altered son of “Big Boss,” himself a fabled warrior. You are told at the start of the game that terrorists have occupied Shadow Moses Island, a government weapons complex, and are holding a pair of high-ranking government officials hostage. They are demanding that the United States hand over the remains of Big Boss’s corpse and one billion dollars; if they don’t get what they want within 24 hours, the terrorists plan to launch a nuclear weapon. To compound the drama, the terrorist group, Special Forces Unit Fox Hound, is your old unit, and its leader has a codename eerily similar to yours: Liquid Snake.

The stakes of Metal Gear Solid, in other words, are high (definitely the most impressively high of any game I had played up to that point in my life — Kid Chameleon this was not). As you (Snake and the player) enter the base via an underwater passage, it’s impossible not to feel the gravity of the situation. You are just one man against an army of genetically-modified soldiers, an army led by your own unit, a unit which now employs deadly assassins with names like “Revolver Ocelot” and “Sniper Wolf.” It’s terrifying, but it’s also thrilling. You proceed to deliver on the promise of your mission by quickly dispatching a pair of sentries (“quickly” only if you played the demo that came with your PsOne a hundred times) and taking a cargo elevator up to the heliport just outside the base. The title screen appears.

At this stage of the game, your sense of purpose is clear, and your ability to get the job done is unquestioned by the player or the character. You have been told again and again by multiple professionals on your codec (several of whom are cute girls!) that the world is counting on you. Even though Shadow Moses Island is an unknown place, and already backed by a creepy soundtrack, your Snake-experience as a soldier, and your player-experience as a gamer, means that you will see this mission through. You have the genes, you have the skills, you have the intelligence, and you have a crack support team. You’ve been no less than perfectly groomed for success — and now it’s time to go kick some ass.

+++

When I first played Metal Gear Solid more than twenty years ago, it didn’t have any particular resonances with my life (beyond, of course, “this is awesome”). As a white middle-class surburban nerd boy in Texas, I couldn’t exactly relate to the ultra-masculine, ultra-competent Solid Snake. I didn’t have any aspirations toward a career in espionage, and I didn’t ever expect to have to singlehandedly defeat a lethal extremist group.

And yet, even in the dorkiness of my young life, there was a mission. Being a millennial came with a set of expectations: expectations of growth, of “delivering” in a way on my parent’s “investments,” of participating in the market society that seemingly every political leader at every level circa 1998 was convinced was the only truly real thing in this world. With those expectations came a certain amount of pressure. Not the pressure that comes from circling around a tank driven by an evil giant and trying to lob a grenade into its hatch… But real, institutional pressures, nevertheless. The pressure to do well at school. The pressure to be involved, always, in and out of class. The pressure to do the things that would look good to future employers. The pressure to never let people down: parents, teachers, coaches, neighbors. The pressure to succeed.

There was a bipartisan consensus in the 80s and 90s about what really mattered, and that consensus (some call in the “neoliberal consensus”) had terms that seemed pretty clear. You’ve probably heard Barack Obama lay it out a number of times. In America, if you try hard, you deserve success. There was disagreement among Democrats and Republicans about who was actually “trying hard,” and about what “trying hard” looked like, who “deserved” anything, etc. But the essence of both major parties’ arguments was the same: if you show your worth to the market, the market will show its worth to you. This individual struggle might not have been always cast in heroic terms, but there was very few American adults who doubted its righteousness.

So the plan was simple. I had a mission, and the goal was the perfect middle-class American life. Getting to that point would be difficult. But if I trusted the system, and did the things I was supposed to do each step of the way, the result was practically guaranteed: I would save the day, like Solid Snake.

+++

The ways Metal Gear Solid confounds your task — the hundreds of twists and turns that leave you (Snake and player) alternately compelled, irritated, baffled, depressed, and furious — are well-documented, and many are famous even to people who have never played the game. But it’s worth nothing how most of the game’s obstacles are not Dark Souls-style challenges that you overcome after gradually learning a foe’s weaknesses, re-tooling your strategy, and executing the perfect run. For the most part, advancing in MGS is the result of… dumb luck. The Heliport outside of Shadow Moses where you so lovingly develop your super-spy skills is just a playground — once Snake is inside the compound, a different, much scarier sort of logic prevails.

The first place where your fundamental helplessness becomes clear is immediately after what seems like an important triumph: your “rescue” of Donald Anderson, the DARPA chief. It is Anderson who first informs you that Shadow Moses is not merely a military base, but also the storage facility for Metal Gear Rex, a “nuclear-equipped walking battle tank.” This revelation seems big, but not terribly surprising (the game is called Metal Gear Solid, after all; the damn metallic dinosaur appears every time Snake sets foot on a battlefield) — it’s the kind of massive obstacle that still seems surmountable, providing you bring your “A-game.” What’s far more shocking — and far less easy to get over — is when the DARPA chief has what appears to be a heart attack right in front of your eyes. He cries out, clutches his chest, and collapses to the ground. Snake places his fingers on the DARPA chief’s neck and shakes his head. “Hmm,” he grunts. “Dead.”

The aforementioned PSOne demo ended here, at this place that is simultaneously a cliffhanger and a strikingly abrupt conclusion to the first chapter of Metal Gear. I had played the game up to this moment dozens of times before finally acquiring the “real” disc, and the codec call immediately after the chief’s demise so stands as one of my most vivid MGS memories.

“Naomi! The Chief? What happened?” Snake roars.

Naomi — the resident “mysterious and sexy” doctor of your support team — is confused. “It looked like a heart attack…”

“A heart attack,” Roy Campbell, your old Colonel, and apparently a trusted (if very gruff) friend, says. “No…”

“COLONEL!” Snake yells. “Are you hiding something from me?”

The Colonel insists that he’s telling you everything he knows. “The Secretary of Defense has operational control,” he says. “I’m just here as your support.”

Snake frowns.

“We don’t have time to debate,” the Colonel says. “Get out of there and find President [of Armstech, a weapons manufacturer] Baker.”

The call ends.

This sequence will play out dozens of times over the course of MGS. Snake will experience something truly terrible that seems to cast doubt on the very purpose of the mission. His support team — sometimes Campbell, sometimes Naomi, sometimes his old trainer, “Master” McDonnell Miller — will reassure Snake that, even though what happened was strange, he can’t lose sight of his mission. The call will then end and Snake will essentially concede the point, continuing “the mission” where he left off, sneaking through what seems like increasingly narrow and “tracked” corridors toward villains that apparently know exactly where to find him. (Ashly and Anthony Burch note in their excellent “Boss Fight” book on MGS that the freedom you seem to experience in the game’s opening stretch is mostly an illusion: this game is finally about as linear as Earthworm Jim.)

Even as the situation changes — even as “friendly” characters tell you lies, again and again — you and Snake are expected to continuing playing by the rules established early on: you sneak, you shoot, you crawl (and thereby severely limit your perspective). Meanwhile, Shadow Moses is permitted to do whatever its warped-genius creator, Hideo Kojima, desires. It can prevent you from reaching out to an important character unless you consult the back of the video game’s box. It can expect you to switch controller ports (to stop a floating psychic from “reading your mind”) with barely a single hint about this wholly unprecedented “strategy.” It can ask — no, coerce — you into doubling back several times just prior to the game’s conclusion to “warm” and “freeze” a card key that you are told will deactivate Metal Gear REX.

That card key, of course, brings REX to life.

+++

According to Malcolm Harris, author of Kids These Days, the best way to view the millennial generation is the same way that corporations have since the beginning: as “human capital.” From elementary school to college and beyond, millennials have been trained to acknowledge and abide by the rules of global capitalism. In the late 80s and through the 90s, the system worked — just look at the GDP! — and the millennial generation was designed to keep it working. The millennial generation thankfully didn’t seem to mind: though much has been made of millennial disruption (“they’ve killed NAPKINS, goddammit they’ve killed napkins!”), the generation’s truly salient quality is probably obedience — to specific authority figures, for sure, but also to a broader conception of what is right and wrong about their country.

No figure is probably more central to the continuing millennial belief in a sort of functioning America than Barack Obama. In the midst of a global recession that could have (should have?) been paradigm-shattering, a young senator from Illinois emerged to capture the hearts of young people. Obama was a beautiful Gen-Xer with a beautiful Gen-Xer wife, deeply familiar not only with the culture that would shape millennial aspirations, but also a student of American history and ideas. His call for “change we can believe in” was nonspecific and mostly nonideological; it was less a revolutionary mandate than an acknowledgement of a sort of mystic force that will always exist and will always carry America toward a better future. Hip but politically astute, sharp but almost always earnest, Barack Obama was the ideal messenger for the ideal neoliberal message: believe in the system, and the system will figure things out.

He was, in short, the millennial whisperer. “Don’t worry. I’m here. I’m cool. And I listen to rap, just like you.” Barack Obama, like Colonel Campbell, was our friend. He wouldn’t lie to us, or hide things from us. He was telling us only what he knew. It was up to us, as millennial Americans, to carry out the mission. Alone. But with helpful advice via codec.

+++

So you aren’t as free or as powerful or as capable as you thought you’d be. So your dreams of a world as a jungle gym will never be realized. So people lie to you and take you for a fool and order you around and seem to delight in your confusion. Life is hard. There’s no use in complaining about it, and you certainly can’t change things. The only thing you can do is just keep moving. Even if the mission becomes unclear, even if your original motivations for completing the mission are totally screwed, you must see it through.

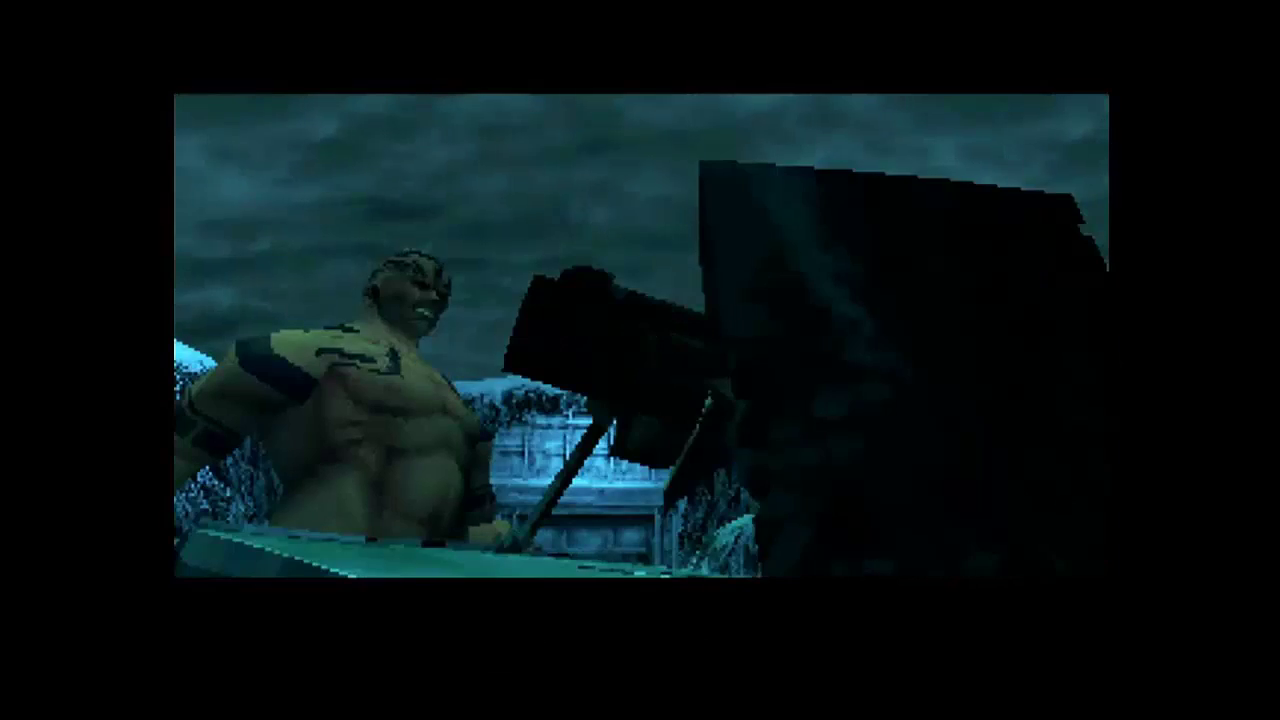

At the start of Metal Gear Solid, Snake appears to be in control. He is a secret agent, and he has agency; though he is working on behalf of the government, the decisions he makes as he winds his way through Shadow Moses seem to be his alone. And then he watches as Baker, the second hostage he was sent to rescue, suffers a fate identical to the DARPA chief’s. And then we watch (Hideo Kojima has tons of fun with perspective, often at the expense of his characters and the players of his games) as Snake passes by Vulcan Raven, a fearsome member of Fox Hound (one who we assumed had been destroyed after Snake BLEW UP HIS TANK), and misses a crucial piece of dialogue.

“Well Boss, I hope you’re happy. He got the card [to open security doors].”

“We’ll play with him a little longer,” his boss, Liquid Snake, replies.

The competing forces in Metal Gear Solid might have different goals for Snake, but the way they treat him is the same: the hero of the game is a pawn. Just when you think you’ve figured out enough to finally have a say, you are triple-crossed. Even those things you think you are doing for yourself have been carefully designed in advance; you’re only important as a vessel for other people’s ideas, most of them nefarious.

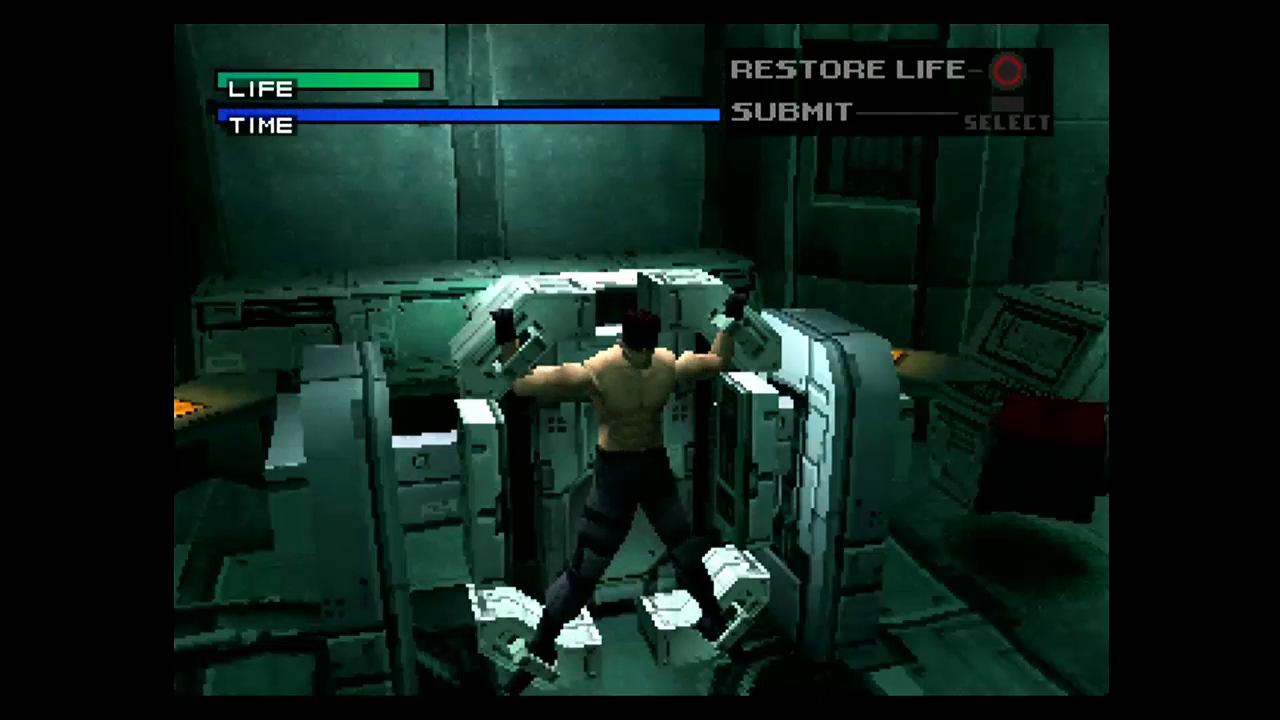

There is just one moment in Metal Gear Solid where your actions as a player have a true impact on the later events of the game. After what appears to be a triumphant defeat of another Fox Hound member, Sniper Wolf, Snake is ambushed. Out of nowhere appears Sniper Wolf — like Raven, not dead, despite your best efforts — who knocks you out and hauls you all the way back to the beginning of the game. You are then stripped half-naked, manacled to a rack, and brutally tortured by a sadistic, pistol-packing mustache man named Revolver Ocelot. Ocelot informs you that Meryl — your de facto partner, and Colonel Campbell’s niece, who was shot by Sniper Wolf and apparently captured — will die unless you can withstand a series of electric shocks. “There are no continues, friend,” he sneers.

This is your choice, really the one choice you have in the game. To kill or not to kill your partner.

+++

The system failed us, and we should’ve been disillusioned. And yet, the era post-recession and pre-Trump wasn’t exactly brimming with countercultural energy. Barack Obama was still in charge, and the sense of righteousness (please do your best to ignore the hundreds of thousands of deportations, scores of children obliterated via drone strike, never ending conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, a completely untenable wealth gap, a country gradually cleaved in two by endless culture wars, etc) was still, therefore, intact. There were brief flares of anger and bitterness; the uprisings in Ferguson, Missouri brought attention to the oppressive American racial hierarchy, the salience of which the President himself seemed eager to downplay. But even those flares were easy to psychologically squirrel away as something other than the system itself — what happened to Michael Brown was not the result of policing as an institution or American racism, but of some “bad apples” whose behavior could be altered with a few simple common-sense reforms.

Donald Trump’s ascendance seemed like a horrible rupture in the peaceful fabric of American society. But in fact, his election (and his ensuing first term) were more the predictable result of a nation riven with grievance and thoroughly brainwashed against the idea of care. Donald Trump didn’t tell us anything about ourselves that a careful reader of history didn’t already, sadly know. The story Obama represented was nicer, but the tale Trump told — a tale of racism, xenophobia, and anti-outsider animus of all kinds — might have been truer. He peeled off the mask of American decency to reveal the cruelty, self-righteousness, intransigence, stupidity, and greed that had been simmering just beneath the surface, barely disguised the whole time.

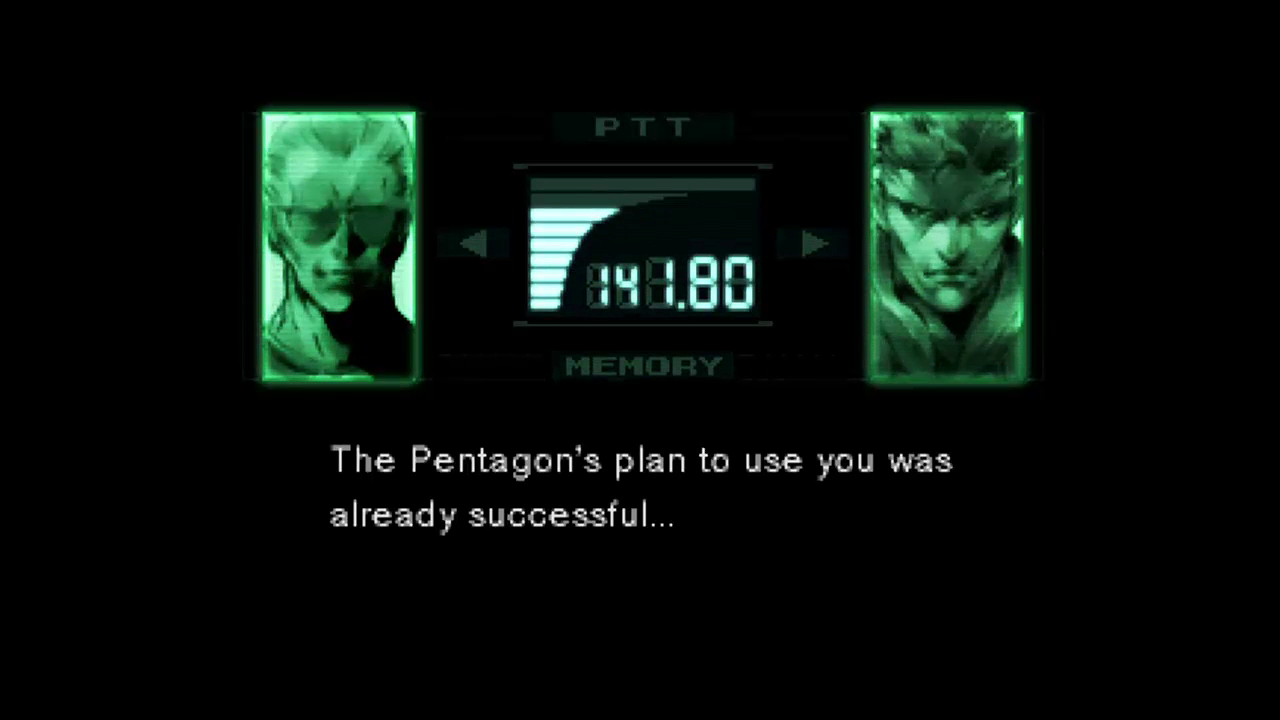

Maybe the most memorable betrayal in Metal Gear Solid occurs, like every other defeat in the game, immediately after what should be a victory. It’s near the end of your adventure, and Snake is standing in the same room as Metal Gear REX itself. After an arduous journey back-and-forth through the underground tunnels of Shadow Moses, he has finally retrieved the “third card key” (a “warmed” version of the PAL card). He sneaks into the control room and inserts the key into its accompanying console. As REX shudders to life, Snake shouts in disbelief, “I deactivated it!”

Suddenly, the Codec rings. Strange: it’s not the Colonel or Naomi or Otacon (the nerdy scientist you rescue and befriend early in the game) on the other end, but Master Miller, whose role in the game’s proceedings has been fairly limited thus far.

“Thank you, Snake,” he laughs, in a voice that is familiar, but not his. “Now the detonation code is completed.”

“Master, what’s going on?” Snake asks.

Your “friend” proceeds to tell you a bunch of things he probably shouldn’t know: about how “they” could learn the DARPA chief’s code on their own. How they decided to “use” you to discover the code — how they tried to use Decoy Octopus, undercover as the DARPA chief, to pry it from you.

“You mean you had this planned from the beginning?”

“Huh?” Master Miller replies. “You didn’t think you made it this far by yourself, did you?”

He laughs at you. “Snake, you’re the only one who doesn’t know.”

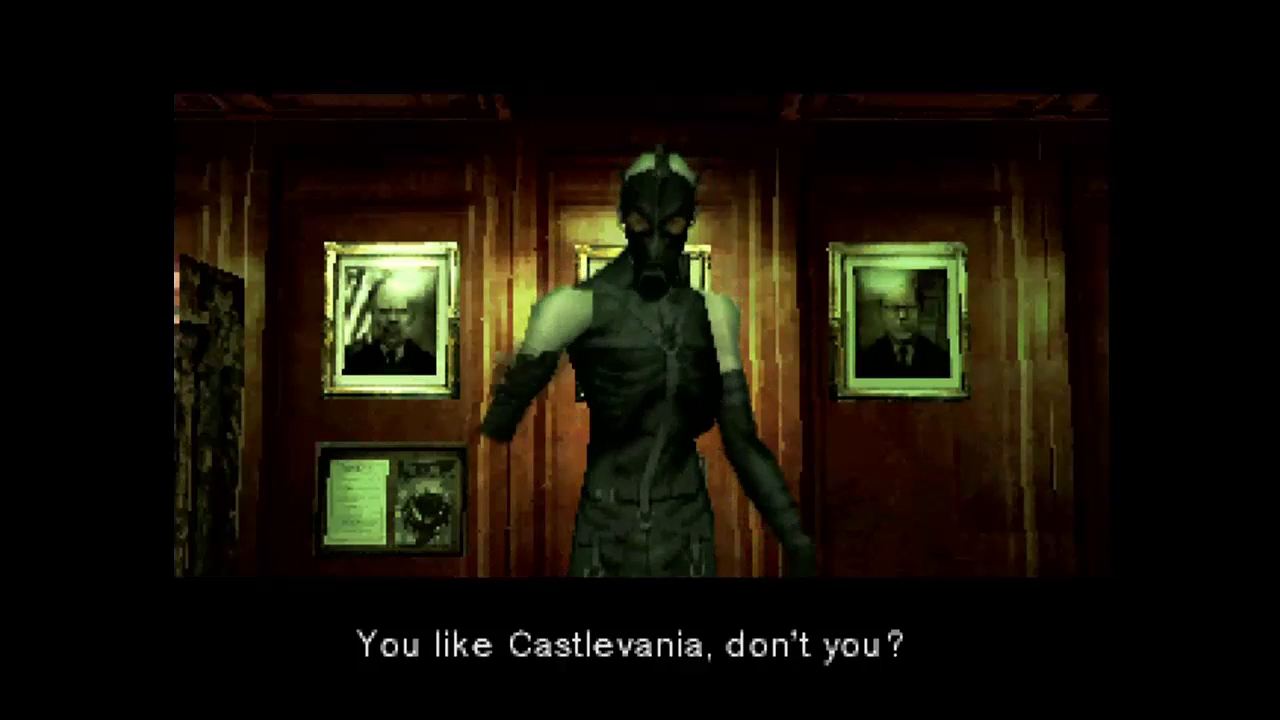

Snake, as ever, seems to only grasp the most basic implications of this conversation. “Who are you anyway?” he growls. The player, meanwhile, has already figured it out. We don’t need Campbell to tell us that “his transmission signal was coming from inside the base!” (though the delivery of that line is perfect). “Master” removes his sunglasses (that was the disguise — a pair of fucking sunglasses) and undoes his hair and reveals the face of your nemesis… your genetic brother… Liquid Snake.

It’s an unforgettable sequence, staged in a way that’s classic Metal Gear — someplace in the middle of corny, hilarious, and scary. But at that point, the fact that a minor character has been feeding us “bad tips” over the radio throughout the game (though, in fairness, “follow the mice” made sense) is just gravy. The game’s most truly disturbing revelation comes earlier, from a different Codec personality.

+++

As the journalists Heather Alexandra and James Clinton Howell have noted in their in-depth articles, the Metal Gear Solid series has always explored the disjuncture between “player” and “character.” The tension between what you are doing and feeling on your couch at home and what Solid Snake is doing and feeling “inside” Shadow Moses is something that clearly fascinates Hideo Kojima, who references it throughout MGS with simple fourth-wall breaking (“Press the Action button to climb the ladder, Snake”) and more nuanced, thematic moments (as when Liquid Snake famously tells Snake, and you, that he/you “enjoy all the killing”). Kojima seems especially interested in areas where you, the player, must do something to proceed in the game, even if it runs contrary to what’s healthy/safe/rational for Solid Snake, the character.

Well before Master Miller reveals his true, inexplicably British form, he reaches out to you about Naomi Hunter, the doctor who has provided Codec support alongside Colonel Campbell throughout your mission. As you go back-and-forth through Shadow Moses, warming and freezing the card key, Miller develops a theory: that Naomi is actually a spy, and that she’s been attempting to sabotage the mission from within.

“Snake,” Miller/Liquid says. “Have you ever heard of something called ‘FoxDie’?”

You have. Liquid was talking about it. It’s some kind of virus. One that apparently targets specific victims and results in something that looks like a heart attack (the exact fate of Decoy Octopus and Baker, the Armstech president).

“Try to remember,” he continues. “Did Naomi give you some kind of injection?”

She did.

Oh shit.

You decide to ask Colonel Campbell about it. He tells you that Naomi has been placed under arrest. Fine. You’re ready to continue with the PAL card…

“But Snake,” Miller interjects, “you might be infected too, you know.”

“All I can do is leave it up to the Colonel,” Snake says, ending the call.

Snake has just been informed that one of his closest allies has betrayed him, that he harbors a deadly virus that has already killed at least two people, and that he, too, could get sick and die. And his response is to just keep on keeping on.

Is this persistence? Madness? Perhaps Snake has been so thoroughly duped by so many people up to this point, the question of who he is working for and what he’s doing for them doesn’t even matter anymore.

Naomi herself contacts Snake “on a different Codec” to try and clear the air. She reveals her mysterious origins; an orphan in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), Naomi’s earliest human connections were with Frank Jaeger, aka Snake’s former ally-turned-nemesis Gray Fox, and Big Boss, aka Snake’s former commander-turned-nemesis-turned-father. “You killed my benefactor and sent my brother home a cripple,” she states, and she has sought revenge ever since. Her chance came with this mission — but she wasn’t the one who made the decision to infect you with FoxDie.

For the first time, you are told the truth: “You were injected with FoxDie as part of this operation.”

Shadow Moses, Metal Gear, the “terrorist threat”: in a flash, all of it is rendered meaningless. The mission that seemed so righteous has suddenly become utterly sinister. In Metal Gear Solid, you are not a hero: you’re a lab rat. It’s not enough that you’ve never been told the truth, and that you are constantly unwittingly performing deeds on behalf of the villains — your very self-definition has now been blown apart. You realize, in this moment, your utter deficit of power, of worth, of basic morality.

The Colonel silences Naomi before she can tell you more. Get back to work, he says. “Right now your job is to stop Metal Gear! Okay, Snake?”

+++

If America gets out of 2020 alive, it might be similar to the way Solid Snake leaves Shadow Moses: in a massive explosion following a frantic chase, and only after the deaths of hundreds (thousands?) of working people, some of whom are your closest friends. The Coronavirus pandemic has been harrowing even in countries with sophisticated, caring welfare systems. In the United States, which has only the most threadbare, patchwork pretense at such a system, it has been simply devastating. It has cast the brightest light yet on problems that have only been exacerbated in its wake: our crippling inequality, our cruel healthcare “arrangement,” our unresponsive federal government, our failure to serve vulnerable populations in any meaningful material way.

Taking the pandemic seriously would require us to stop and reverse several prevailing trends in American life. Comprehensive healthcare, as provided by Medicare for All, and some kind of jobs guarantee or a Green New Deal might help to alleviate mass suffering. Unfortunately, neither major presidential candidate in the 2020 election has proposed any such plan to tackle the pandemic, and neither seems interested in resolving any of the crises that have only worsened Covid (and that will continue to exist when (if?) the virus is contained). Bernie Sanders did support such plans, but he was never able to secure the sort of millennial votes that he needed to best Joe Biden in the primary season. We say we want “change” — we loved this word when Obama whispered it to us — but we’re still doing the things that perpetuate and worsen “the system.” Our mission is still on a track, and the track finally forces us to help the villains.

Snake is haunted throughout Metal Gear Solid by a sword-wielding, hand-amputating, gravelly-voiced cyborg ninja. You learn early on that this mysterious presence in fact a hideously regenerated Gray Fox, the aforementioned “brother” of Naomi Hunter and a complex figure in Snake’s own life. Sometimes your ally and sometimes your enemy, the ninja/Fox seems to function as an eerie prediction of what Snake could become, or maybe even an eerie criticism of what Snake already is: a battle-wrecked, vengeance-hungry mutant that lives only for more killing. He speaks mostly in opaque aphorisms, but his final words to Snake, just seconds before being crushed by Metal Gear REX, have a meaning that’s unmistakable. “Snake!” he bellows. “We’re not tools of the government, or anyone else!”

The line’s power is complicated by the fact that, up to that point, it’s fair to argue that both Snake and Fox have been “tools of government.” So what exactly is Fox saying? That soldiers have to assert their agency? That your mission must constantly be interrogated by your conscience? That it’s not enough to play along — that at some point, you’ve got to kick back against the forces that surround you, even if that action seems hopeless?

I don’t know. Maybe I’ll call Colonel Campbell and find out.

Comments

Post a Comment